First Tier Ranks—

As mentioned in chapter 1, the role of Imperial Guardian was the highest civil office at this time with the role of Regent-Marshal as the highest military office. There was no “Prime Minister” (Chengxiang or Xiangguo).

As the guardian of the heir apparent, the Imperial Guardian was a key figure in selecting and guiding the emperor’s successor. The Usurper Wang Mang (45 BC-23 AD) was the Imperial Guardian and Regent of the last Former Han Emperors (Western Han) before he seized the throne.

He Jin, brother of the Empress, was the last Regent-marshal, or Dajiangjun. The position had been held in the Later Han by a member of the empress’s family. After He Jin’s death, there was no Regent until Cao Cao assumed the role, and the highest military position was General of Chariots and Cavalry.

Li Jue took the title of Regent-general, or Dasima, but it is not a standard title of this period. During the Han it alternated with that of Grand Commandant, or Taiyu. In the Former Han the Regent was called Dasima, and that may be why Li Jue, as the Emperor’s caretaker, assumed it. The title here is used retroactively. The official appointment by the Emperor occurred after he took the title for himself.

The Qin and Former Han title of “Prime Minister” was restored in this period. After establishing Emperor Xian, Dong Zhuo had himself elevated to the position, and because the office is closer to the sovereign than any other, Cao Cao later assumed it himself. He formalizing it eighteen years later in 208 and coupled with the elimination of the three elder lords (sangong), it was a milestone in the history of the imperial bureaucracy (Roberts 1991).

According to Dong Zhuo’s biography in the Sanguozhi, along with the position of Prime Minister he acquired the following offices before putting Emperor Xian on the throne: Sikong (Minister of Works, one of the sangong), Taiyu (Grand Commandant, one of the sangong); and he took possession of the instruments of command over the Imperial Tiger Escort. After the imperial government’s removal to Chang’an, Dong Zhuo was both Prime Minister (xiangguo) and Imperial Preceptor (taishi).

Second Tier Ranks—

Huangfu Song, who was pivotal in the suppression of the Yellow Scarves Rebellion, was rewarded with the title General of the Flying Chariots—in the Roberts translation, the title of General of Chariots and Cavalry. It is comparable in status to General of the Flying Cavalry first awarded to honor a daring foray into Xiongnu territory. It is a military title second only to that of Regent-Marshal (Roberts 1991).

There were honorary lordship appointments called “Guannei” or “Guanzhong Hou”. The Hou Hanshu states: “These ‘lords within the passes’ have no territory but are supported by the revenue from the counties in which they live. The amount of tax revenue is determined by the number of households.” The title is sometimes translated as “Lesser Marquis” (Roberts 1991). I have also seen the title named “Secondary Marquis.” Zhang Liao was appointed a Secondary Marquis by Cao Cao when he recruited this commander after the fall of his master.

Regional Tier Ranks—

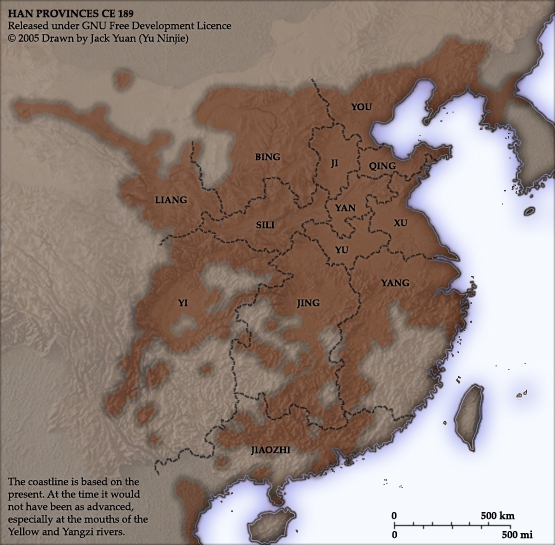

Those not directly involved with the Imperial government were assigned regional titles. Imperial Protector was the highest office in an administrative region or zhou. The regional title of Protector had relatively independent authority; whereas, the Imperial Inspector was more strictly answerable to the court. Weakening central authority in the last Han reign is reflected in the increasing number of Protector appointments over Inspector appointments (Roberts 1991). Ancient China was divided into nine regions and each region had a capital city, often of the same name. Over time, more regions were created to bring the number up to twelve as discussed prior.

As referenced in Shiji, “Wei jiangjun piaoji liezhuan:” Protector was a provincial appointment at a compensation rate of 2,000 piculs of grain per month. Typically under the Han, the customary chief provincial officer was the Imperial Inspector at 600 piculs. A traditional Asian unit of weight, defined as “as much as a man can carry on a shoulder-pole” with a modern standard of 60.5 kilograms. Additional records add: Historically, during the Qin and Han dynasties, the stone was used as a unit of measurement equal to 120 catties (160 pounds in 1885). Government officials at the time were paid in grain, counted in stones. The amount of salary in weight was then used as a ranking system for officials, with the top ministers being paid 2,000 stones.

Sources:

Roberts, Moss (1991). Three Kingdoms: A Historical Novel. Mao Lun/Mao Zonggang recension edition translated by Moss Roberts.